If organic chemistry had an Olympic event, it would involve finding the easiest way to synthesize natural drugs. Some routes have 30 or 40 steps, and the yields are horrendous because of side reactions all along the way. Various chemists have become organic rock stars by streamlining a synthesis to only a dozen or so steps.

However, though the bench artists bring elegance to the field, a much larger group has more of an engineering mindset – whatever works, and it needs to be fast and cheap. Hence there’s been talk for years about getting genomes to do the work instead. After all, genes make the enzymes that form nature’s production line. And gene work imposes fewer hazards from solvents and the like. But it’s not trivial. Some enzymes need to be in a certain type of operating environment or in a certain spatial relationship relative to other enzymes. And we don’t always know which genes are involved in making the enzymes in the first place.

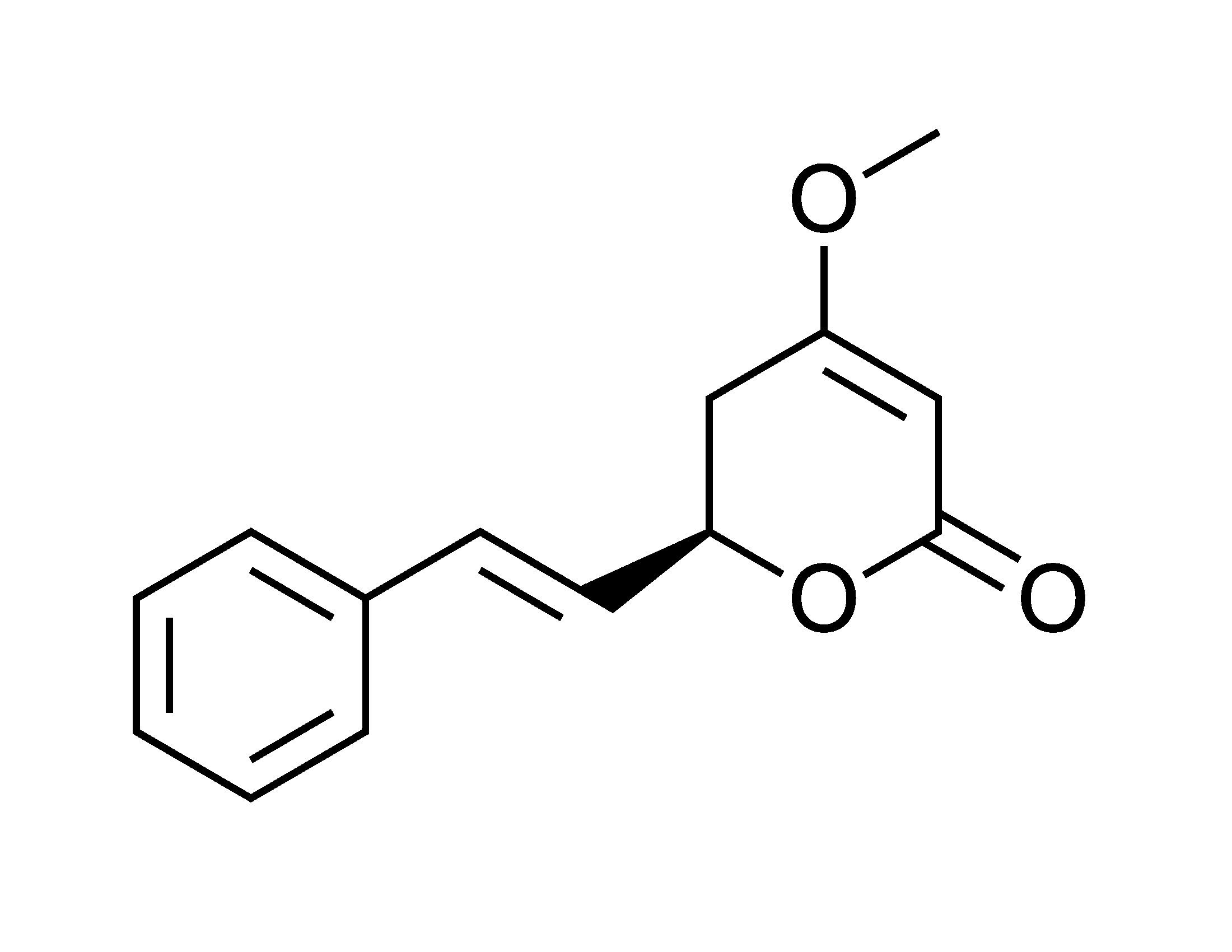

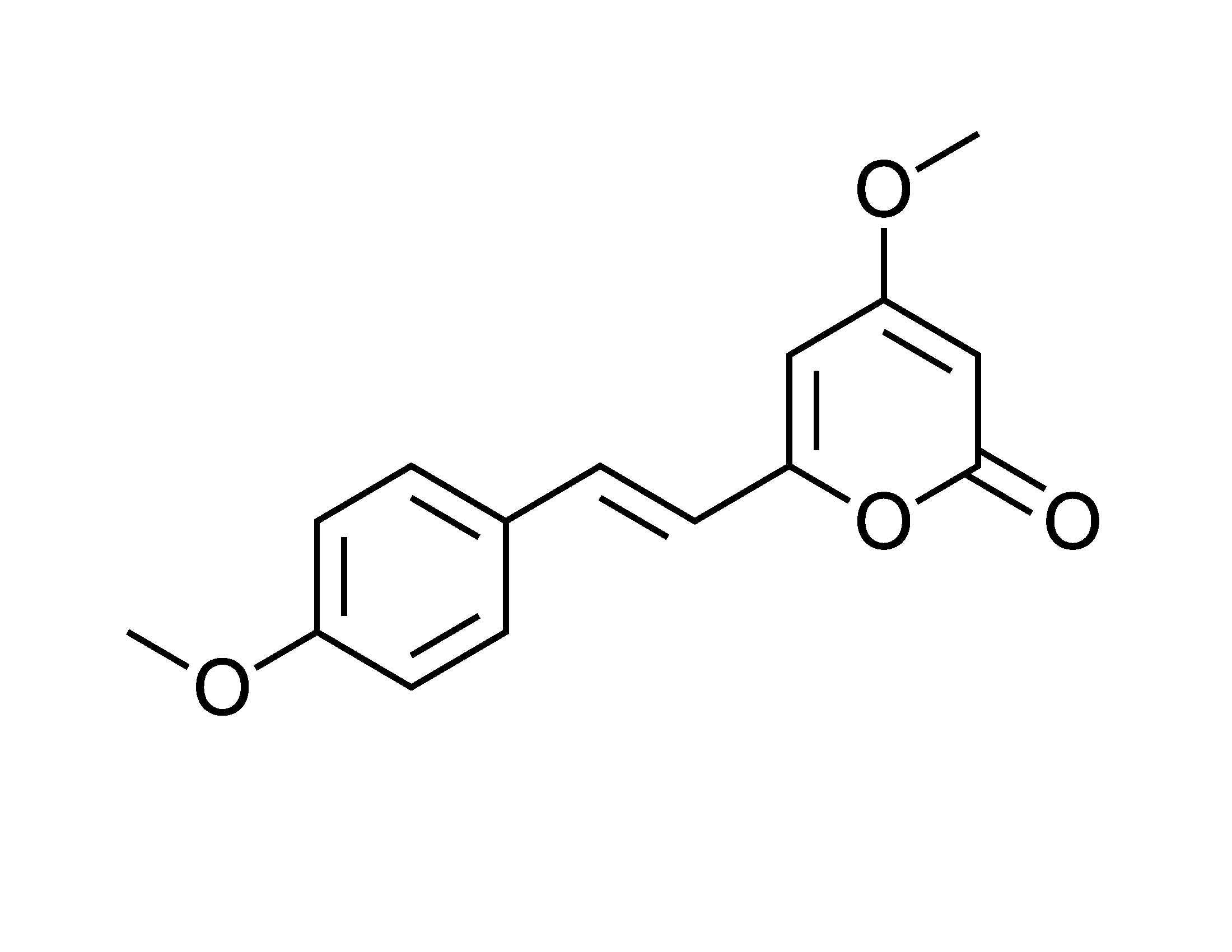

Biologists at MIT (Jing-ke Weng, Tomáš Pluskal, and their group) are making progress on this. Their recent work is on some of the simpler natural drugs, presumably to shake out the approach before tackling hairier molecules. And their latest coup is engineering bacteria to make kavalactones – the relaxing components in the drink kava. Kava, for ye with botanical leanings, is Piper methysticum in the pepper family. The extract of interest comes from the root. It has six main kavalactones, of which kavain is predominant.

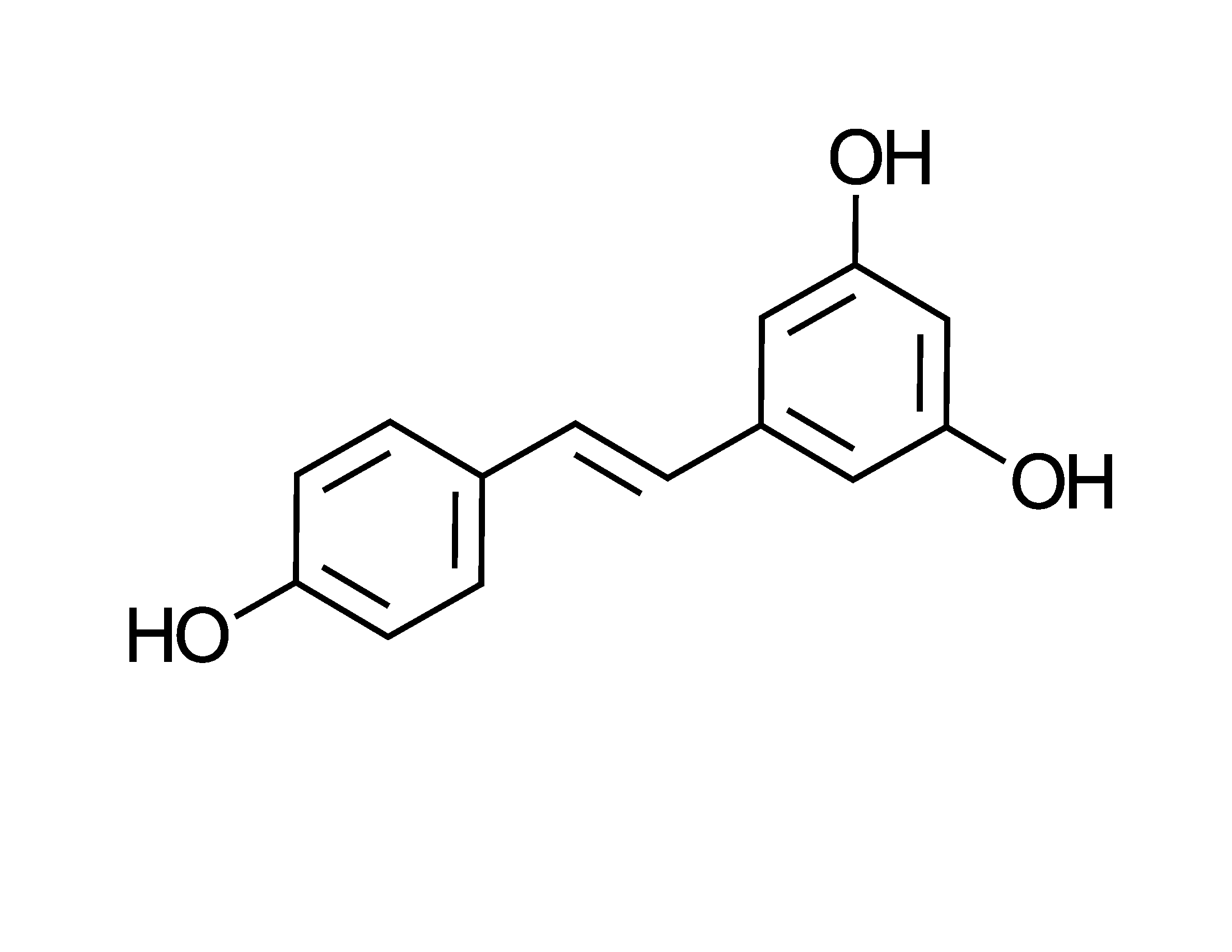

Basically, the compounds are the inverse of caffeine, and even fish relax when they’re exposed to them. Hence the drink provides a substitute for alcohol but without the aggression. If you know a mean drunk, you might want to introduce them to this stuff. Interestingly, kavalactone structures are evocative of the chemical class known as stilbenes, and as such are analogs of resveratrol from grapes. Comparisons to the fruit of the vine have a structural basis.

Now somebody could cite an ugly little acronym, GMO, for the engineered bacteria that produce kavalactones by the new scheme. However not all GMOs represent a rampage in the wild. Bacteria can be cultivated easily in sealed conditions, as in fermentation tanks for yogurt. When the harvest is ready it’s a mere matter of isolating the chemical jewels either from the broth or for instance from dead biomass. And with this method discovery of a potent new natural drug maybe be less likely to leave the host plant on the endangered list – a concern that became very real with taxol.

A critic has noted that the current focus on individual compounds is simplistic: kava is in fact a complex mixture, as are many other natural substances. If the goal is an experience that completely mimics that from kava, I’d agree. But in my mind a far bigger point is that the medicinal industry is ready to make the next leap in drug production. It couldn’t come at a better time, considering the ongoing gold rush to discover new drugs in nature. I doubt that historic synthetic approaches can even come close to keeping up with the rate of discovery. Here’s to living factories for medicine. Cheers!

Food for Thought