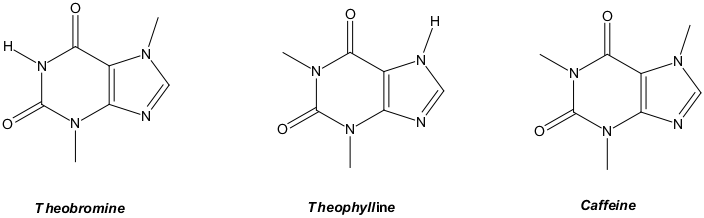

Last week I speculated on chocolate supplements to fight COVID. If you recall, both tea and chocolate are sources of theobromine. Since then I learned of disputes over statements on Facebook. It seems that a page attributed a tea-cure theory to Dr. Li Wenliang, who treated early COVID, yet there’s no record that he ever said it. The Facebook item also cited tea compounds (methylxanthine, theobromine, and theophylline). The rebuttals note that a tea-cure lacks medical evidence, and that these compounds affect patient airways, and say that only antiviral drugs treat viruses.

The original chemical list there is redundant, so its expertise is doubtful. Methylxanthine is a generic term for theobromine, theophylline, and caffeine, among others. But the rebuttals are no better. They rely on flawed logic and missing facts. Fine, it’s fair to say that there’s no evidence. That’s normal for a new theory. But there’s also no evidence that it won’t work.

In fact, the critics so far don’t seem to know the science. As an example, green tea is antiviral against flu (as is cocoa), HSV, enterovirus, rotavirus, Epstein Barr virus, and HIV. Yet those infections persist, so clearly “antiviral” doesn’t necessarily mean “cure”. There the main effect is likely due to polyphenols that hinder attachment of the virus to human cells; once a beastie attaches, they likely can’t stop it from replicating inside the cell. But our focus is on dilute theobromine that may play a role in viral replication and might help with a cure. As of yet, I’m unaware of theobromine-specific tests against COVID or other viruses, even in petri dishes.

I’d also noted that antiviral drugs (vs. vaccines) have key structural analogs to theobromine, and both affect physiology. I could also add, teas have anti-cancer effects, and those mechanisms are related to anti-viral effects. Admittedly, theobromine is a long shot against COVID, but everything is a long shot until it’s tested. Most new ideas don’t work.

So, we come to gut-checks. With tea-drinkers and chocolate-eaters, we’d expect lower COVID rates or shorter duration in those demographics. Then why don’t we see a slam-dunk in Asia, a major tea-consuming region? It may reflect a need for more theobromine than tea-lovers get from their ordinary habits, just as my calculations found the concentration is too low.

In any case, I’d looked into theobromine-richer dark chocolate. Those inferences are also limited. Chocolate is popular, but how many people eat much of it daily? That small group would be our study population. And there’s a control issue: variation in natural products. Good suppliers test and mix herbal batches to guarantee threshold concentrations of medicinal natural compounds. I don’t recall seeing theobromine quality control on labels for normal chocolate.

Turning to the molecular level, in synthetic antivirals the chemically bonded sugar (ribose) component appears to help the alkaloid (nucleobase) portion get carried to our cells’ genetic factories. However, I’ve seen nothing that says free theobromine isn’t transported to genetic factories, too. In fact, we know that an analog, caffeine, slides between helical turns of DNA and RNA. So, it’s clear that unmodified alkaloids do get there.

Here somebody could argue that if theobromine really works in the same way as synthetic antivirals, then overdosing on the stuff should produce carcinogenic mutations. However, the polyphenols in tea have anticarcinogenic properties, so the effect could be masked. Chocolate has a similar polyphenol profile, so maybe we should limit the biostudies to theobromine itself.

Bottom line? The theory is not yet disproved. Naysayers should cite data and interpret it strictly within its scope. Otherwise their own inaccuracies are just as bad as what they quench.

*******