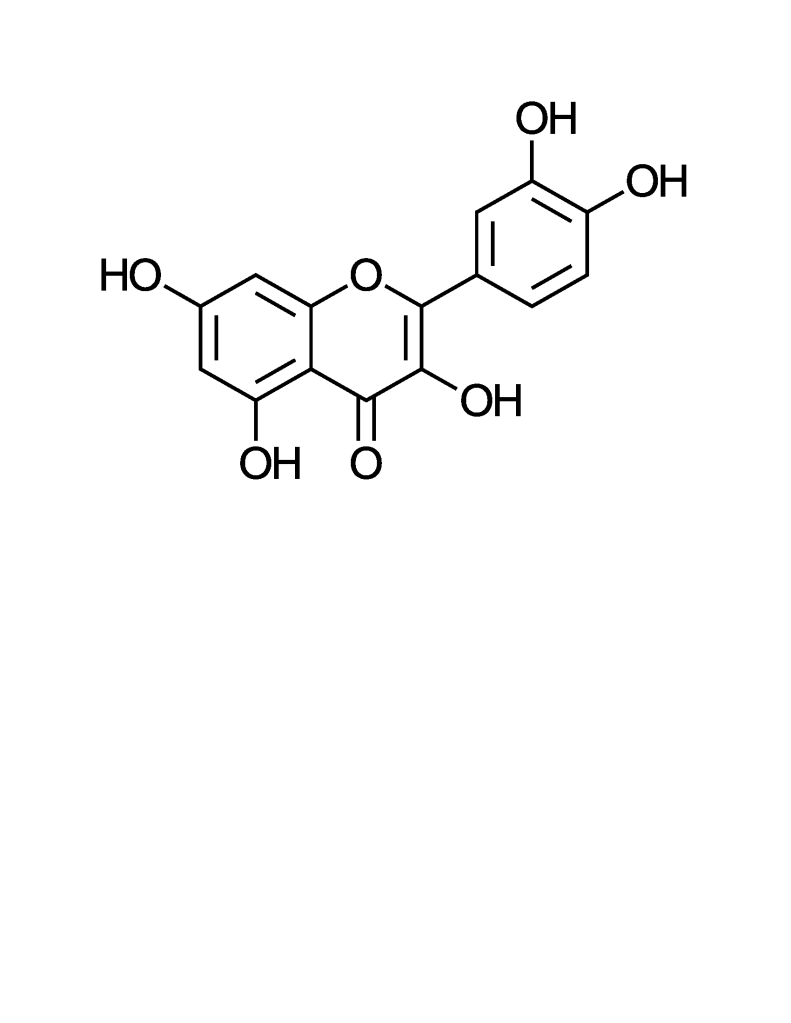

Sometimes the medicines for a new type of crisis are already in the pantry. A preprint posted last week compares the computational fit (“docking”) between COVID proteins and a library of about 8,000 compounds. The library includes synthetic antiviral drugs as well as natural compounds from traditional Chinese medicine. One goal is to skip safety testing, since these compounds already have a history. Here, a green tea component is among the winners.

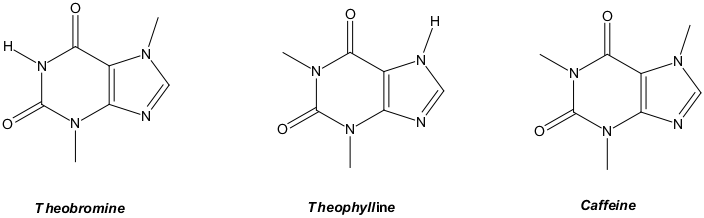

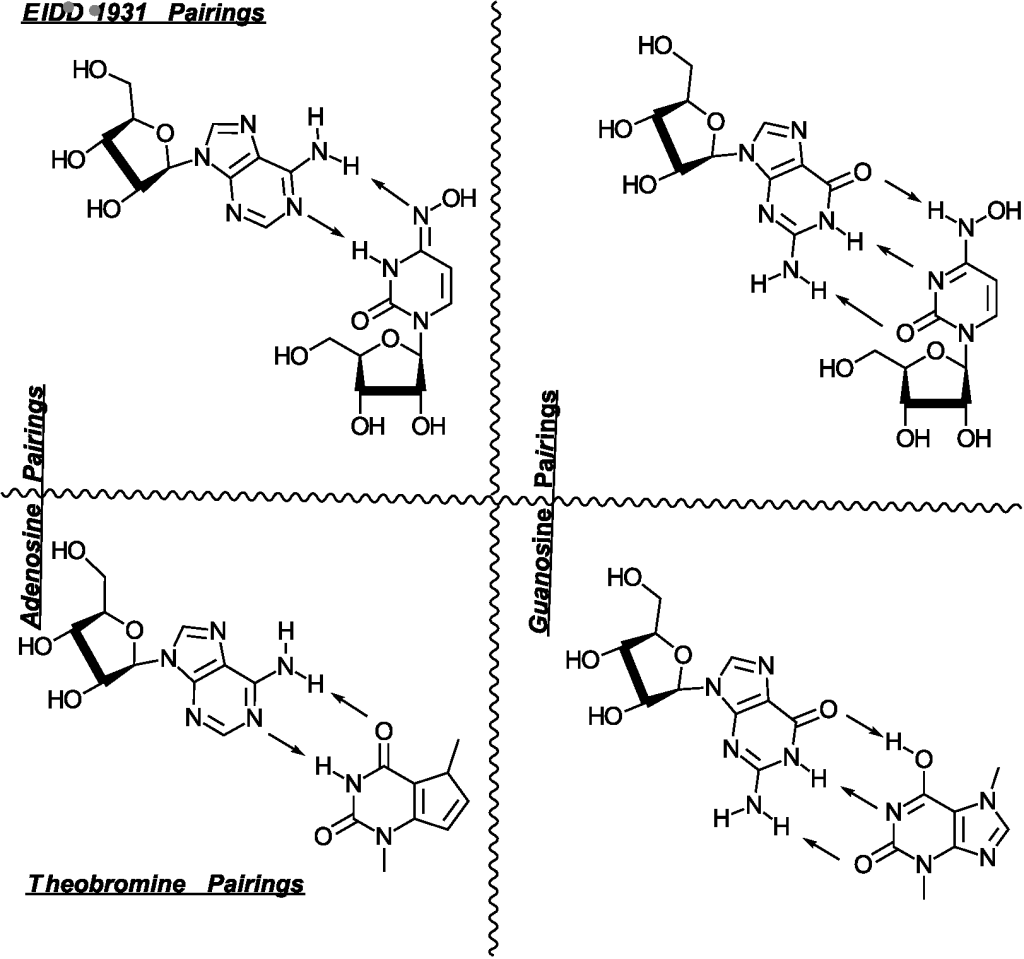

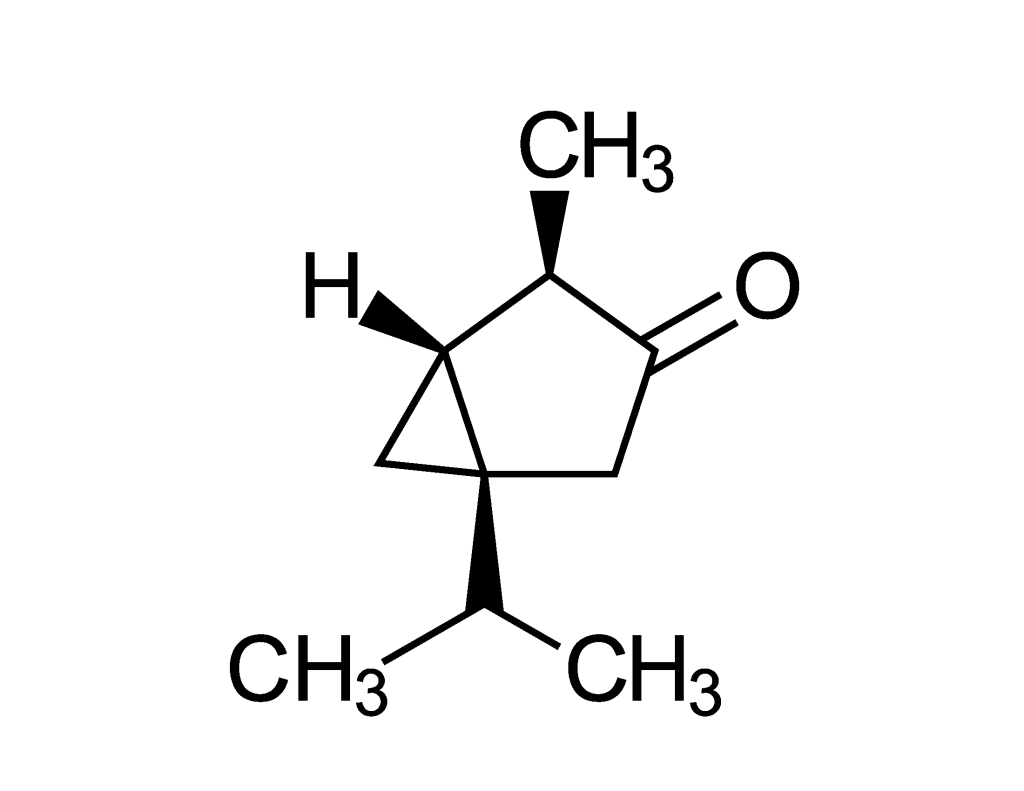

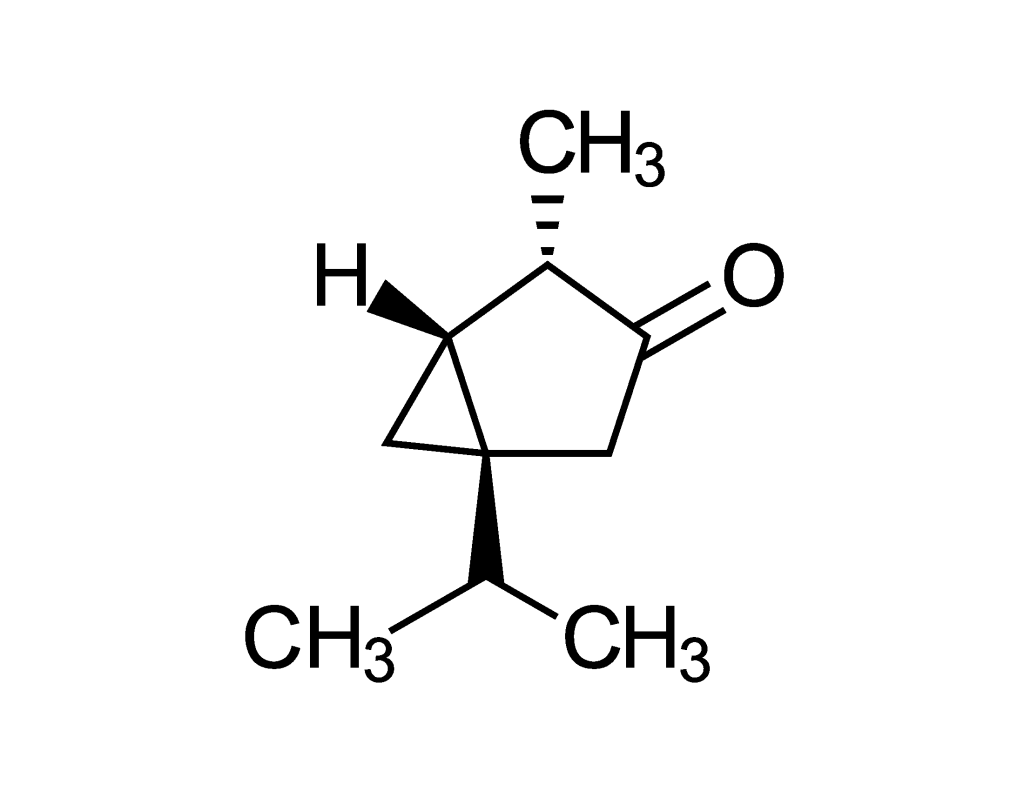

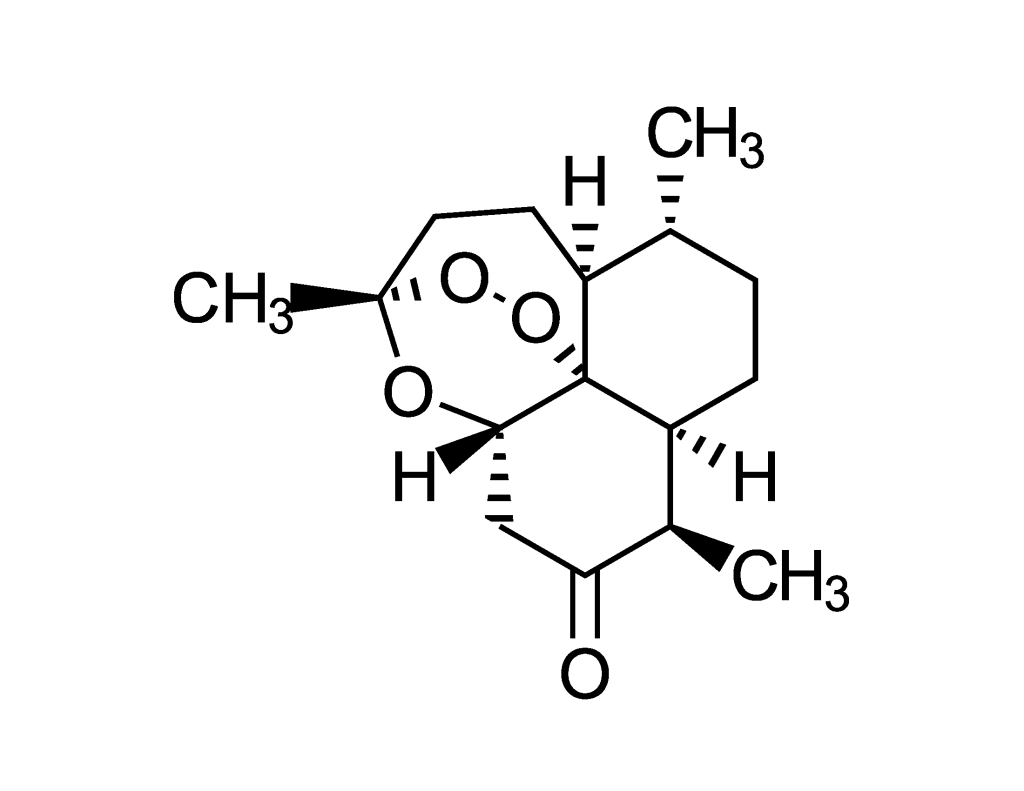

That’s good, because the other highlighted natural compounds have big downsides. (1) LSD-related Metergoline docks very well to COVID spike (attachment) protein. (2) Lobeline (from plant genus Lobelia) has a narrow safe therapeutic range; it’s an addiction cessation drug and docks to spike protein and non-structural proteins. (3) Bicuculine (from Corydalis species) causes epilepsy effects; it docks to non-structural proteins. (4) Caffeine and (5) theophylline didn’t do well against COVID proteins; the paper didn’t give results for theobromine.

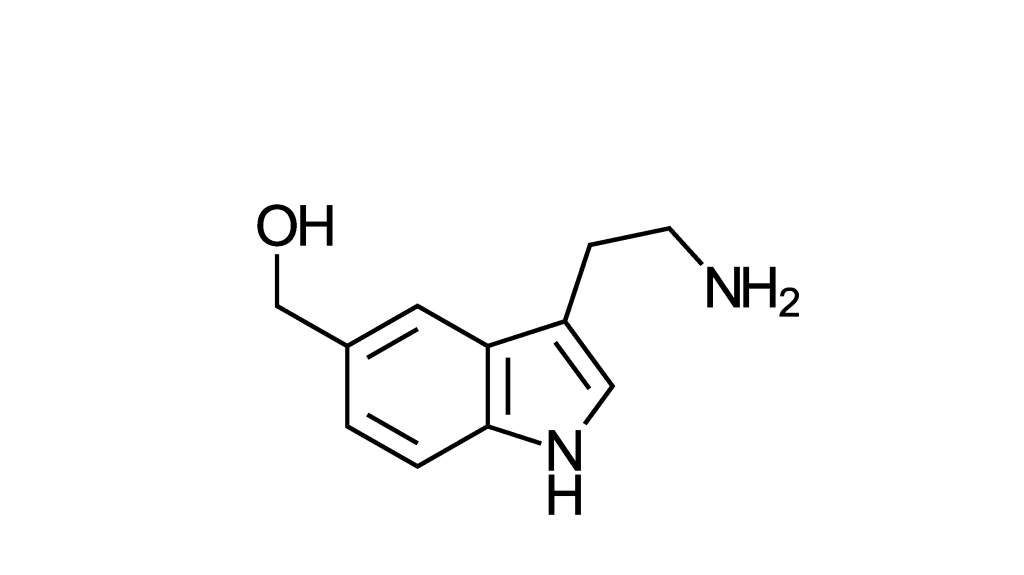

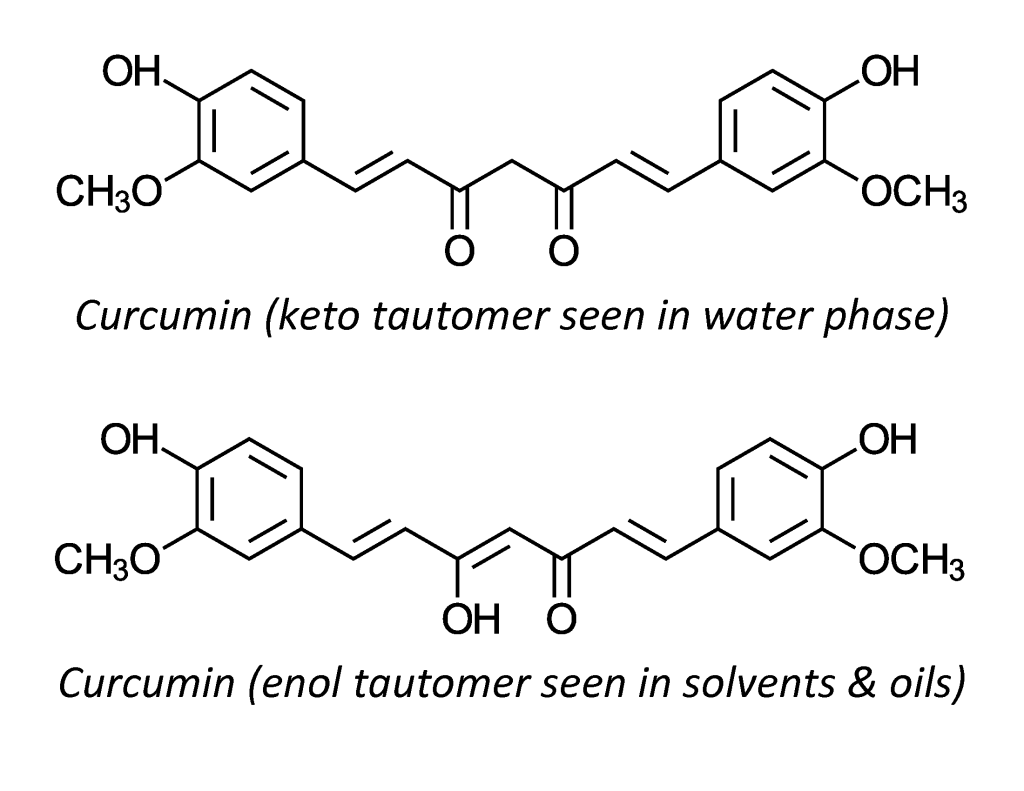

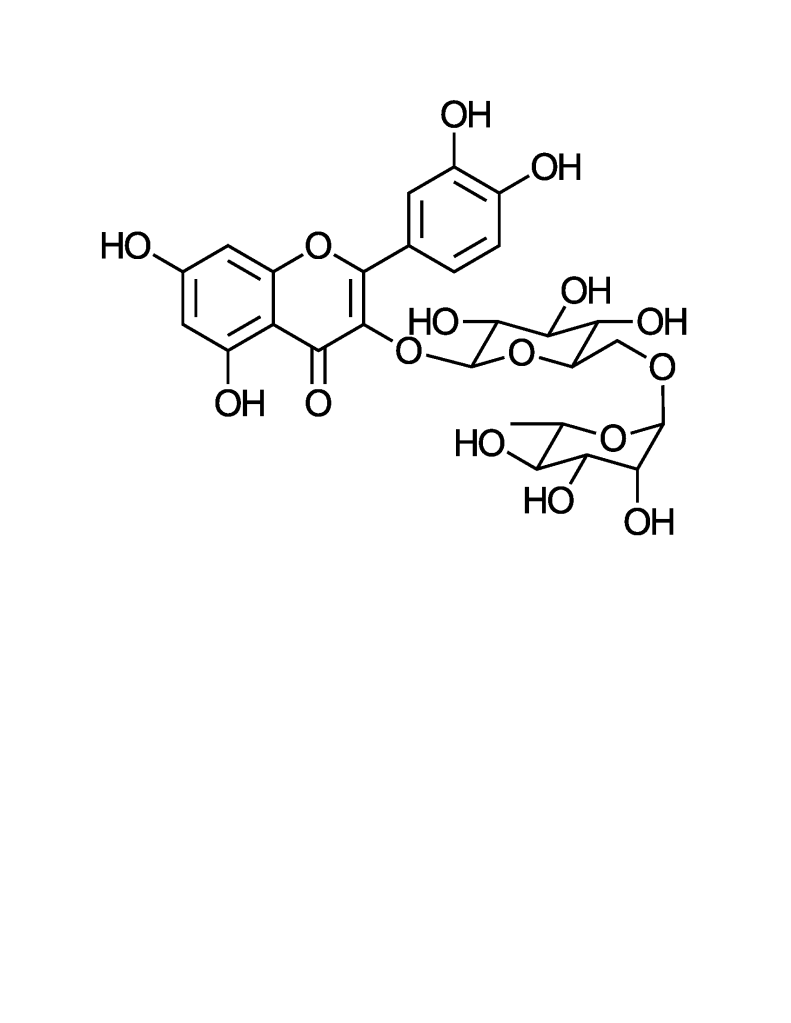

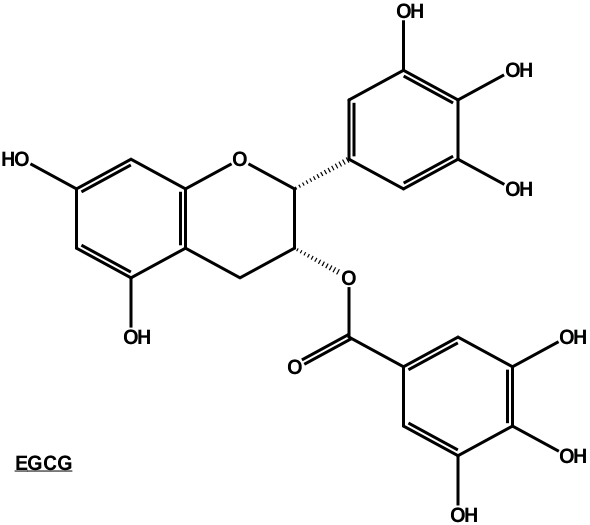

The catechin EGCG (epigallocatechin gallate) was more promising. Computer models found that it binds almost as well to the spike protein as synthetic antivirals do (modestly well) and was in the top 5% of test molecules for binding to non-structural proteins. As a reminder, catechins are a class of natural chemicals. They’re not the stringy seed-bearing catkins we see on some trees. Many plant-based foods have EGCG, but green tea is the leader. EGCG is also in: other teas, fruits (especially berries), tree nuts, dark chocolate, red wine, and legumes. It’s a potent antioxidant, antiviral, and anticancer agent, and is also among my favorite molecules.

The anticancer aspect has been a quandary because green tea results are impressive in test tubes and animal trials, but mixed or weak in human trials. My *guess* is that the analysis there underestimated the bioavailability hurdles, and that this is relevant for antiviral effects also. Only 10% of ingested EGCG and related catechins reach the blood; the other 90% passes through the gut or into its microbes. EGCG also doesn’t stay in the blood for long: the peak concentration is under 2 hours after ingestion and the half-life is 5 hours. Yet ways to boost it are known.

- Choice of brand: most green tea leaf brands have EGCG in the range of 25-85 mg/cup (8 oz.). Lipton has 71 mg/cup, and is economical. Teavana Gyokuro Imperial Green Tea has 86 mg/cup, but is pricier. Celestial Seasonings is also said to be respectable.

- Choice of type: for readers who are *really* into tea plant science, check out the loose-leaf website below. It seems that Camellia sinensis var. Sinensis teas (such as Chinese and Japanese teas) have more EGCG than do Assamica teas (of India, Vietnam, and Chinese Yunnan), and that shaded varieties (e.g., Gyokuro, matcha, and kabusecha) are richer than non-shaded. Second-harvest (meaning fall, vs. spring) and leaves near the bud are catechin-rich. Teas from the Chinese Zhejiang region are also, but Japanese teas often surpass the Chinese levels. And steamed teas have more EGCG than do pan-fired teas.

- Number of cups: Depending on whom you ask, EGCG is safe at 500 – 800 mg/day. The safety issue is less about EGCG, and more about other substances or contaminants.

- Preparation: EGCG is bitter. Green tea connoisseurs and bottlers avoid that by using moderate steeping temperatures (~160°F or ~70°C), but this robs the tea of some medicinal value. To leach EGCG from the leaves the water must be at or near boiling. A recommended steeping time is 10 minutes. The bitterness can be lightened by citrus or other juices, or by mint flavors, honey, stevia, spices, floral essences, etc., or diluting with ice. Don’t add milk or cream, due to their protein content (keep reading).

- Drink the tea between meals. When taken with food, the catechin concentration in the blood is lower by 60-75%. Presumably this is because catechin phenolics get complexed with dietary proteins. If you’ve seen milk curdle when adding it to tea, you’ve seen that.

- Let the tea rest in your mouth before swallowing it. Catechins pass through cheek tissue directly into blood, but they need time to get absorbed. Don’t dawdle *too* much: EGCG survival time in the mouth is at most 20 minutes, which is much lower than in the body. By the way, brewer’s yeast improves absorption by mouth tissues for substances in food.

- Green tea extract (solid). This concentrates water-soluble tea compounds (including EGCG), to get the equivalent of extra cups of tea per day. But don’t get excited. Unless you drink it, taking an extract bypasses absorption in the mouth. And EGCG’s dwell time in the blood is only an hour or two, so sipping all day may be better than taking pills.

- Injection of EGCG into the blood. This might raise blood levels of EGCG, but would require a prescription.

- Nanotech is under study by various groups for oral EGCG delivery.

*******

Food for Thought

Z. Wang, C. Xu, B. Liu, N. Qiao, “Repurposing the natural compound for antiviral during an epidemic – a case study on the drug repurpose of natural compounds to treat COVID-19,” (preprint submitted 5/19/2020) https://chemrxiv.org/articles/Repurposing_the_Natural_Compound_for_Antiviral_During_an_Epidemic_-a_Case_Study_on_the_Drug_Repurpose_of_Natural_Compounds_to_Treat_COVID-19/12326399/1

N. Naumovski, B.L. Blades, and P.D. Roach, “Food inhibits the oral bioavailability of the major green tea antioxidant epigallocatechin gallate in humans,” Antioxidants 4:373-393 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4665468/pdf/antioxidants-04-00373.pdf

C.S. Yang, M.J. Lee, and L. Chen, “Human salivary tea catechin levels and catechin esterase activities: implication in human cancer prevention studies,” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention, 8(1):83-89 (January 1989). https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/cebp/8/1/83.full.pdf

Michael Eisenstein, “Tea for tumours,” Nature 566:S6-S7 (2/7/2019). https://media.nature.com/original/magazine-assets/d41586-019-00397-2/d41586-019-00397-2.pdf

Anonymous, “How to choose tea with the most EGCG,” (Simple Loose Leaf Tea Company, 4/26/2019, with numerous citations to primary scientific literature). https://simplelooseleaf.com/blog/life-with-tea/how-to-choose-tea-with-the-most-egcg/