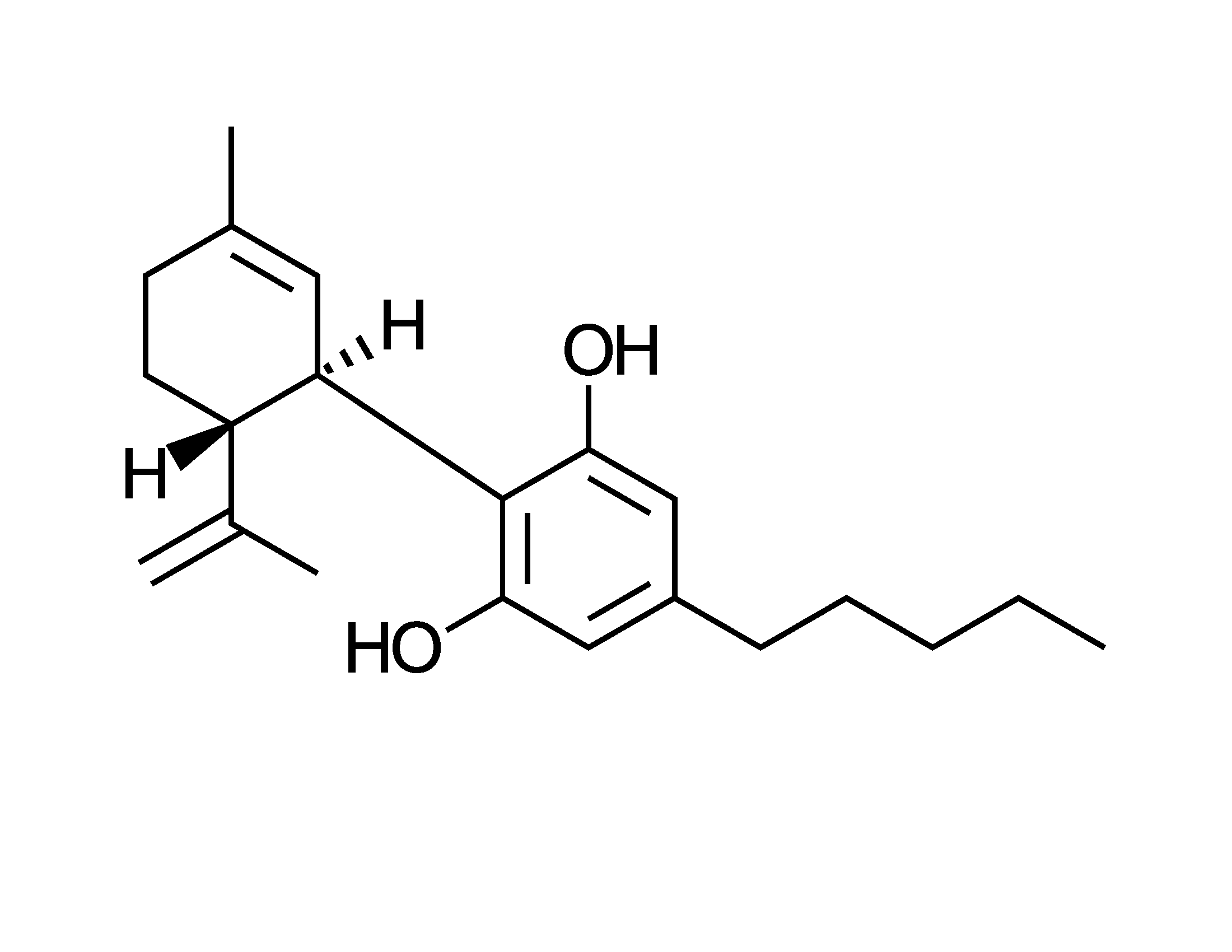

If humans had designed the medicinal arrangements in plants, I’d have guessed that committees were involved. The mixes, and the proportions, often appear whimsical or arbitrary. For instance, tobacco has Snow White and the Seven Dwarves – nicotine and a handful of minor players, some with anagram names such as cotinine. Cannabis has the 101 Dalmations – or 113 according to one count – of which THC is the lead dog. Then there’s ginseng with a handful of ginsenosides, and their pecking order depends on which species is under the microscope.

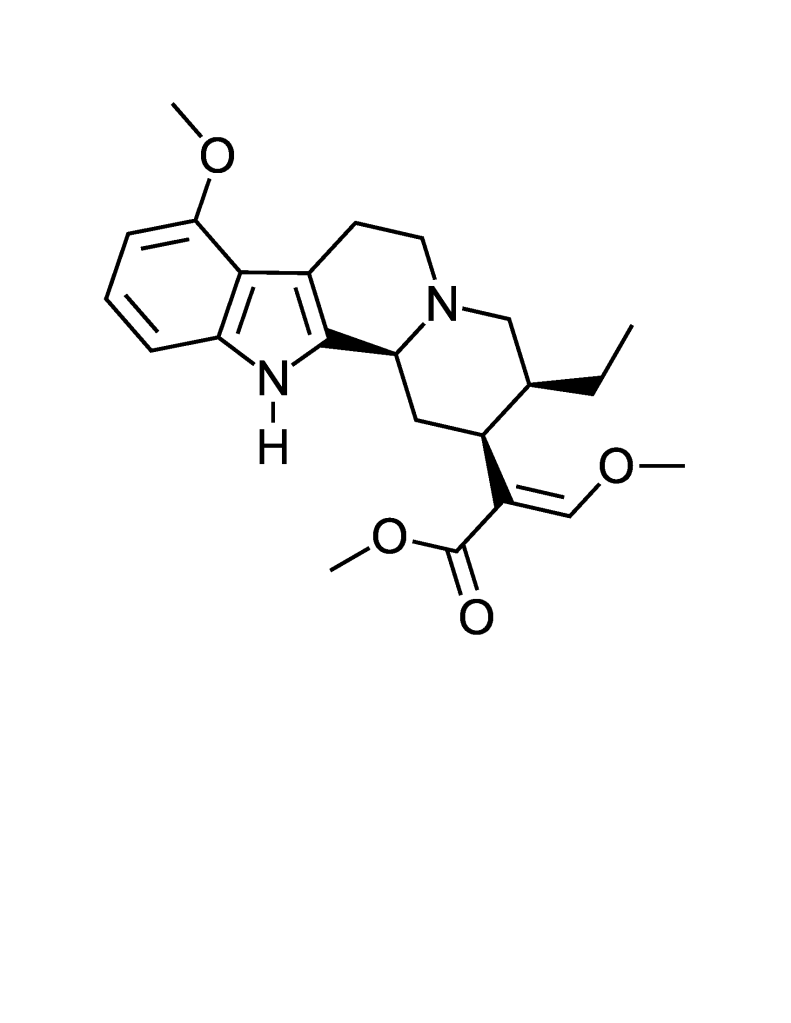

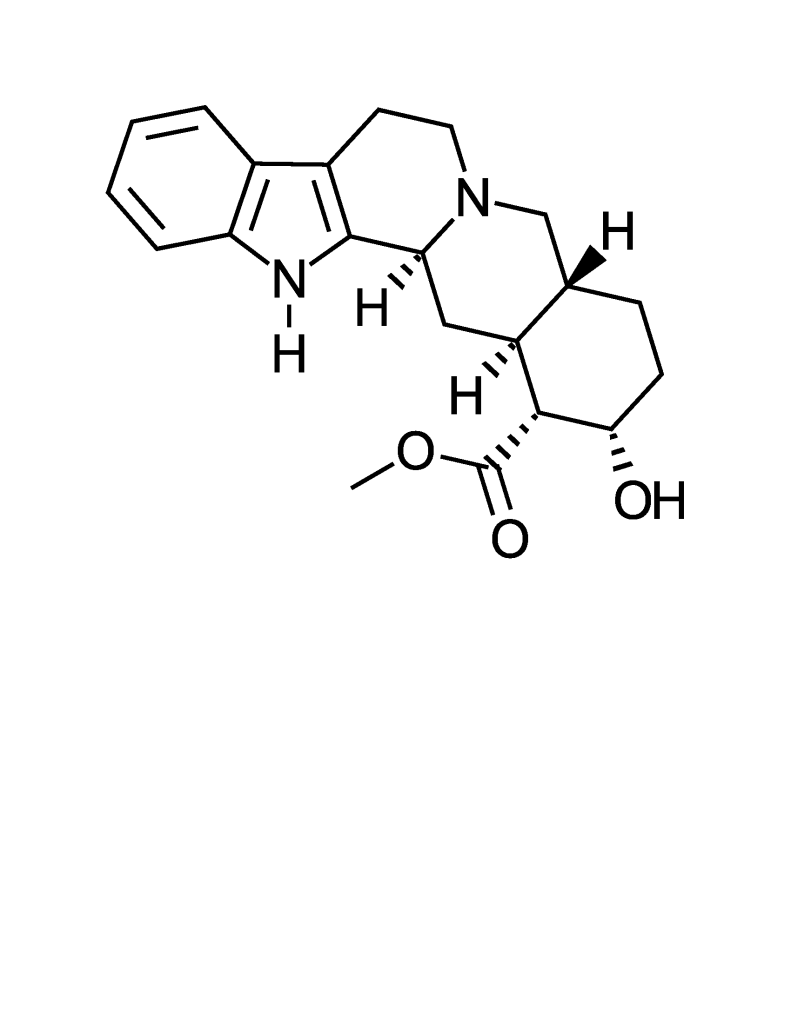

Kratom (the leaves of Mitragyna speciose from Southeast Asia) is in the middle of those, with the indole alkaloid mitragynine as the leader in a blend with ~40 related compounds. Structurally they resemble yohimbine, which is more widely found in nature. Yohimbine, in turn, can affect mood-related receptors (dopamine, serotonin) or have adrenaline-like effects.

No surprise, kratom is controversial. Its fans are several million strong in America, and use it for anything from pain relief or opioid withdrawal to energy boosts or libido. And in fact, kratom is well known to be an analgesic, stimulant and mood booster. Some might call that combination ideal. And yet it has marked side effects. The DEA wants to ban this green powder, the FDA wants to regulate it, and the Mayo Clinic calls it unsafe and ineffective.

Oddly, statistics support both sides of the fence. Contra: the stuff causes addiction, seizures, hallucinations, and psychotic symptoms. Pro: serious side effects seem to be mainly from hyper-doses, at which point all bets are off. Even kitchen spices have a history of abuse. I knew locals in Danbury, Ct, who called themselves nutmeggers; the nickname had colonial origins, when the town imported nutmeg in part to get high. Who knew? But back to the topic at hand. Contra: CDC has reported that coroners found 91 fatalities arose by kratom overdoses in an 18-month period. Pro: an outside study found that using kratom alone kills almost nobody.

That got me thinking about the herb’s alkaloid arsenal. The variations likely contribute to the broad effects. I’m guessing that the same chemical diversity accounts for the low lethality, after all, the herb hits on all cylinders without requiring huge amounts of any one contributor. So kratom’s diversification appears to rationalize both its strength and its failure to kill.

Green plant actives aren’t the only group that use safety-in-number. Lanolin (natural wax from wool, used for skin conditions) is said to have as many as 20,000 constituents due to its combinatorial bonding. Petrolatum (like Vaseline®, from petroleum, derived from ancient plants, and used for skin conditions) has two concentration bell curves: maybe a dozen major compounds spiking up, overlaid on a myriad of minor ones with almost a uniform distribution. This isn’t the first time that natural diversity has struck me as a useful example for drug design paradigms. But this time it’s for other reasons. Hopefully, no matter how the laws turn out for kratom, the drug field will take a harder look at the benefits of complexity and chemical permutations in formulation.

Food for Thought

Sunil Mathur and Clare Hoskins, “Drug development: Lessons from nature (Review),” Biomedical Reports, 6:612-614 (2017).

Posted at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5449954/pdf/br-06-06-0612.pdf

Frank R. Denton III, “Beetle Juice,” Science, 281(5381):1285 (28 August 1998) and 281(5383):1615 (11 September 1998).

Summarized at https://scite.ai/reports/beetle-juice-1y6vWn